Kenya: The Kingdom of Running

Kenya, the world’s 26th most populous country, has dominated long-distance running for decades. But where does this supremacy come from? What historical, cultural, and social forces have shaped generations of champions without interruption? This article opens our summer series on the homeland of marathon legend Eliud Kipchoge.

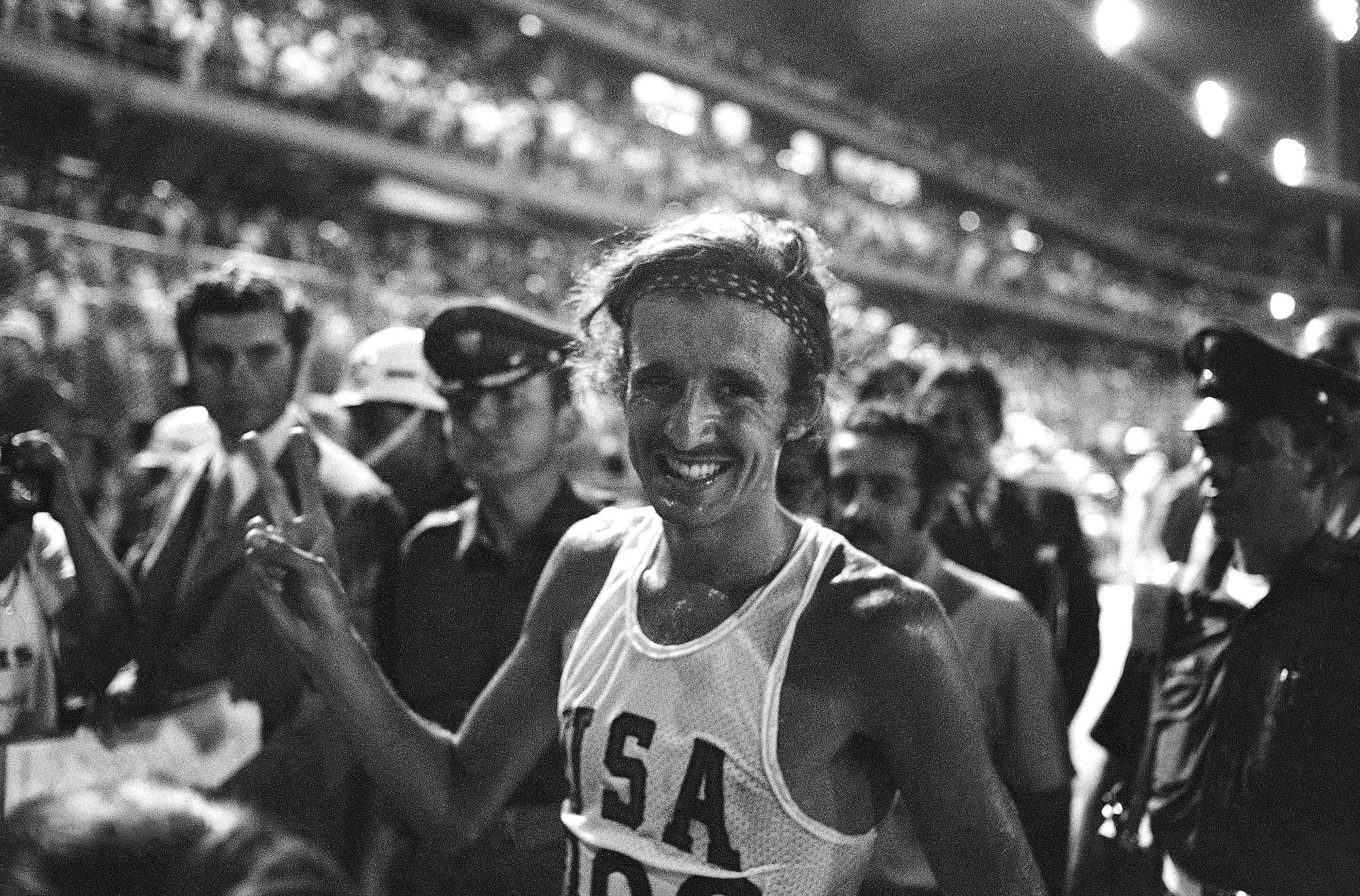

If there’s one country that embodies the spirit of running like no other, it’s Kenya. Even casual fans of the sport know this reputation. The story began more than half a century ago—back in the 1960s, when Kipchoge Keino struck gold in the 1,500 meters at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Keino, who retired with two Olympic golds and two silvers, remains one of the greatest African athletes of all time. More importantly, he ignited a culture of winning that has defined Kenyan athletics ever since. Let’s rewind the clock.

| A Remarkable Story Rooted in a Complex Past

Kenya gained independence in 1963, after a long colonial period—first under German control, then British rule. The origins of Kenyan athletics trace back to the British colonial era. As early as the 1930s, British institutions organized competitions for workers in the army, railway, and postal service. Running was already embedded in daily life—many children ran long distances to school, and physical endurance was part of the culture. The British sporting system simply provided the framework to showcase this natural talent.

The Kenya Amateur Athletics Association (KAAA) was founded in 1951, paving the way for international competition. Kenya made its Olympic debut in Melbourne in 1956, but it was Tokyo 1964 and especially Mexico City 1968 that announced the country’s arrival on the world stage. The steeplechase, once dominated by Europeans, quickly became a Kenyan stronghold thanks to pioneers like Amos Biwott and Benjamin Kogo. Then came Kipchoge Keino—Olympic champion in the 1,500 m, medalist in both the 5,000 m and steeplechase—who launched a dynasty of champions. From there, Kenyan runners extended their dominance from the track to the roads, rewriting the global distance-running hierarchy.

| Building a Structure for Success After Independence

Kenya’s success isn’t just about raw talent—it’s also the product of deliberate organization. After independence in 1963, the KAAA became the driving force of national athletics. It was renamed Athletics Kenya (AK) in 2002. For decades, AK has overseen national competitions, Olympic and World Championship selections, and multiple disciplines ranging from road running to cross-country, trail, and mountain races.

The 1990s saw professionalization accelerate. Many Kenyan athletes earned scholarships in the United States, later competing in lucrative road races across Europe and Asia. At the same time, world-class training camps began to flourish in high-altitude towns like Iten, Kaptagat (home of Eliud Kipchoge), and Nyahururu, all above 2,000 meters. These hubs created an entire “running industry” that has continued to produce elite performances. Competition at home grew so fierce that some runners eventually chose to represent other countries in order to have international careers.

| A Hall of Legendary Champions

Since the 1990s, Kenya has been the unrivaled powerhouse of global marathoning. While their athletes first shined on the track, it’s on the roads that they cemented their legend. The most iconic figure is Eliud Kipchoge. After moving from the track to the marathon in 2013, he has become the defining athlete of his generation. The only man to win three Olympic marathon titles (2016 in Rio, 2020 in Tokyo, 2024 in Paris), Kipchoge also set a world record of 2:01:09 in Berlin (2022), a performance still regarded as one of the greatest athletic feats of the modern era. Rising star Kelvin Kiptum (born 1999) looked set to succeed him. In October 2023, at the Chicago Marathon, he stunned the world with a record-breaking 2:00:35, fueling hopes of the first official sub-two-hour marathon. Tragically, his life was cut short in a car accident in February 2024 at just 24 years old—an immense loss for Kenya and the global running community. Before Kipchoge, another Kenyan great, Paul Tergat, had already made history. A five-time world cross-country champion and rival of Ethiopia’s Haile Gebrselassie, Tergat became the first man to break 2:05, running 2:04:55 in Berlin (2003)—a milestone that redefined marathon possibilities.

On the women’s side, Kenya long lived in Ethiopia’s shadow, but athletes eventually flipped the script. Catherine Ndereba was the first to establish long-term dominance. A two-time world champion (2003, 2007), two-time Olympic silver medalist (2004, 2008), and the first woman to dip under 2:19, she set a world record in Chicago in 2001 with 2:18:47. More recently, Brigid Kosgei has carried the torch. In October 2019, she smashed the women’s world record in Chicago with 2:14:04, eclipsing Paula Radcliffe’s legendary mark of 2:15:25 set in 2003. Kosgei has also claimed two London Marathon victories and remains a perennial favorite at major races. Another modern star, Peres Jepchirchir, won Olympic marathon gold in Tokyo 2020 and is a two-time half-marathon world champion.

| Kenya Today: Glory and Challenges

Kenya remains a global superpower in distance running, but not without challenges. Athletics Kenya still plays a central role, though its governance has faced criticism. The contrast between athletic success and the country’s widespread poverty creates immense pressure. Thousands aspire to professional running careers, but opportunities are scarce, leading to hardship and instability within the sport. At the same time, the running ecosystem continues to expand. Training hubs like Iten now attract not only Kenyan elites but also international amateurs seeking altitude training at 2,400 meters. This form of “running tourism” provides income and global recognition for the region.

But dangers persist. The tragic case of Agnes Tirop—a two-time world bronze medalist at 10,000 m and fourth in the Tokyo Olympic 5,000 m—who was murdered in 2021, exposed the vulnerability of female athletes. Since then, the “Tirop’s Angels” initiative has been working to combat domestic violence and improve safety for women in sport. Yet poverty and fragile living conditions remain deep-rooted issues.

Technically, Kenyan runners now benefit from the best equipment and increasingly scientific training methods. However, they also face growing international competition from Ethiopia, Uganda, Morocco, and even European nations. The future of the Kenyan model rests on a delicate balance: honoring a deeply rooted cultural heritage, navigating the increasingly individual nature of professional athletics, and sustaining a national system strong enough to keep producing champions.

Charles-Emmanuel PEAN

Journalist