Why Is the Berlin Marathon So Fast?

Among all the great races, the Berlin Marathon is perhaps the one that most runners dream of when chasing a personal best. A founding member of the Abbott World Marathon Majors, it has earned a mythical reputation in the running world. And the numbers speak for themselves: 13 world records have been set here. Berlin is nothing less than the temple of speed over 42.195 km. But what makes this race so conducive to extraordinary performances? Let’s take a closer look at the ingredients that make Berlin one of the fastest marathons on the planet.

| A Flat Course Designed for Speed

One of Berlin’s greatest assets is its incredibly flat profile. The total elevation gain is just 73 meters over the entire course—essentially a highway built for marathoners. This allows athletes to maintain an even pace without having to break their rhythm. The result: steadier heart rates, smoother strides, and optimized running economy.

Another advantage is the layout itself: long straight stretches and fewer than twenty turns in total. Everything is designed so runners can stay locked into their cadence without disruptions.

And there’s a subtle extra benefit: the surface. Berlin’s roads are paved with asphalt rather than concrete, which is slightly softer and easier on the joints. As race director Mark Milde explains: “It seems more favorable. Athletes tell us they feel less joint pain here.”

| Nearly Perfect Weather

Late September in Berlin often provides ideal conditions: little wind and temperatures between 12°C and 18°C (54°F to 64°F). Experts agree that the sweet spot for running fast is between 10°C and 16°C (50°F to 61°F)—and Berlin’s historical average sits right in that range, around 15°C (59°F). Coincidence? Not at all—nature lends the city a priceless advantage.

This year, however, forecasts suggest a slightly warmer start than usual, around 20°C (68°F).

| The Weight of History and Records

Thirteen world records have been broken in Berlin. Thirteen! No other marathon in the world comes close. From Kipchoge to Assefa to Sawe, this reputation draws the world’s very best athletes every year, creating unmatched excitement.

Unlike London, where the depth of the field often turns the race into a tactical battle, Berlin follows a different strategy: focus on one or two record-chasing athletes, with pacemakers calibrated to lead them through 30 km. Any more than that, and it becomes a tactical race for the win and prize money—usually resulting in slower times.

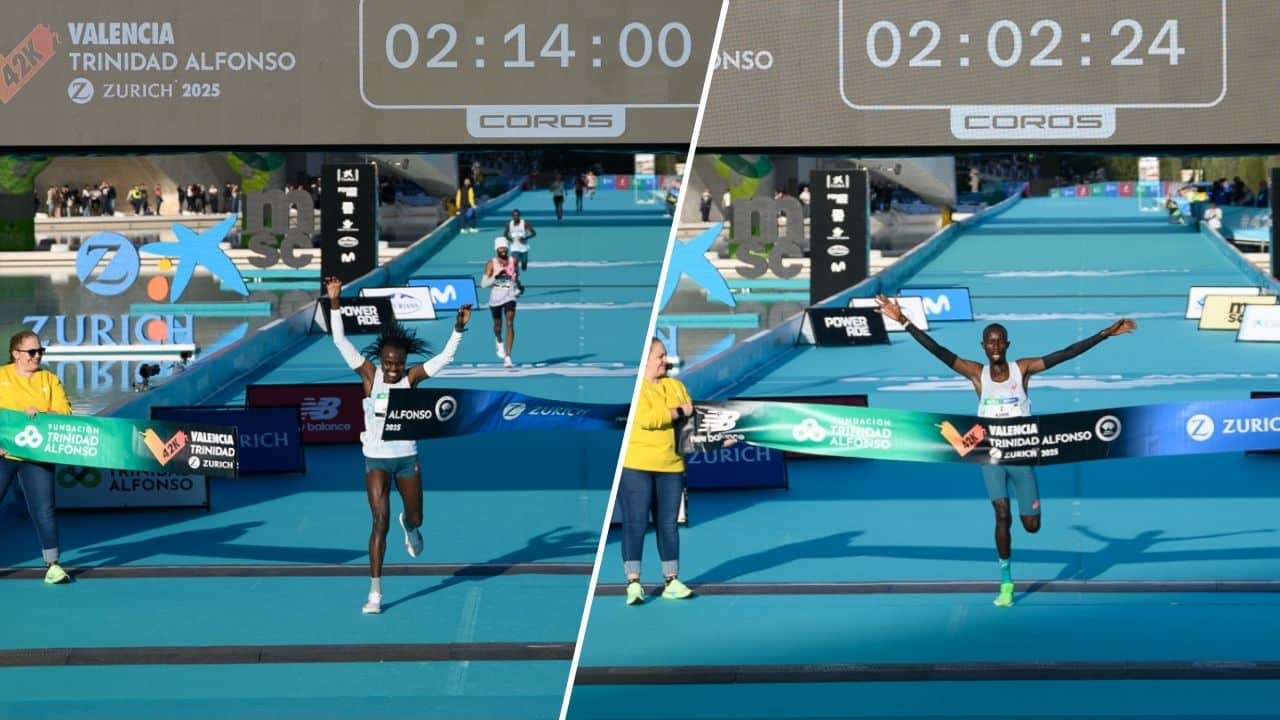

This year’s headliner is Kenya’s Sabastian Sawe, with a personal best of 2:02:05. He chose to skip the World Championships in Tokyo to chase greatness in Berlin. After spectacular wins in Valencia (2024) and London (2025), he arrives in Germany with his sights set firmly on history.

For amateurs, the appeal is just as strong. The Berlin course offers incredible depth—every runner, from the front of the pack to the back, finds themselves absorbed into a steady rhythm within the flow of the peloton.

“I chose Berlin because it’s one of the fastest courses in the world. After running 2:02 in both Valencia and London, my goal is to run the fastest race I possibly can—and of course, if everything goes well, to win it.”

Sabastian Sawe

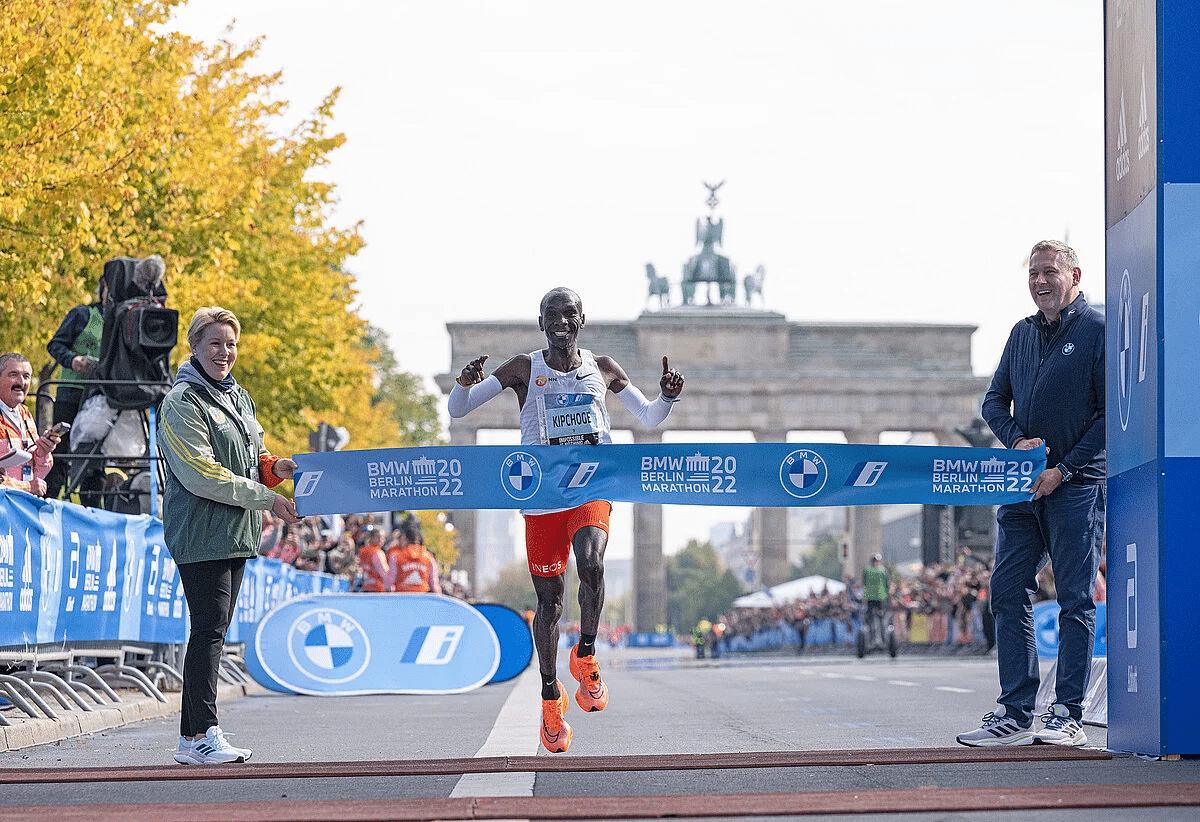

| Kipchoge: The King of Berlin

You can’t talk about Berlin without mentioning the GOAT of marathon running: Eliud Kipchoge. On September 25, 2022, the two-time Olympic champion ran an astonishing 2:01:09, setting a new world record and the second-fastest time in history at the time. It was a masterclass in pacing, made even more impressive by the fact he passed halfway in 59:50 before easing slightly in the closing kilometers.

With five victories in Berlin (2015, 2017, 2018, 2022, 2023), Kipchoge has become the undisputed master of the city’s streets. His 2022 performance remains one of the greatest demonstrations of Berlin’s magic.

| Pacemakers and Precision Fueling

Berlin is also about precision engineering. Pacemakers play a vital role, keeping the pace perfectly even up to 30 km. Thanks to them, many champions have executed record-breaking negative splits—running the second half faster than the first.

But one of Berlin’s lesser-known secrets is its customized fueling system. Elite athletes prepare their bottles the day before, and volunteers are assigned to hand them over mid-race. None is more famous than Claus Henning-Schulke, nicknamed “Bottle Claus.” He became a legend for his enthusiasm and near-perfect handoffs during the 2022 race, when he personally managed Kipchoge’s fueling.

As Kipchoge himself once said: “My greatest memory of Berlin is the man who handed me my water. He is still my hero today.”

Comme le raconte le Kényan lui-même : « Mon plus grand souvenir de Berlin, c’est cet homme qui me tendait l’eau. C’est toujours mon héros aujourd’hui. »

Henning-Schulke describes his role as almost a race within the race. Speaking to Runnersworlds,, he explained: “Imagine—they’re running over 20 km/h. You have to keep eye contact, shout to get his attention, hand over the bottle at the perfect moment. Then you jump on your bike and sprint at 40 km/h to the next station to do it all again. It’s exhausting, but every successful handoff feels like a victory.”

“Imagine—they’re running over 20 km/h. You have to keep eye contact, shout to get his attention, hand over the bottle at the perfect moment. Then you jump on your bike and sprint at 40 km/h to the next station to do it all again. It’s exhausting, but every successful handoff feels like a victory.”

Claus Henning-Schulke, “Bottle man” for Kipchoge

Berlin isn’t fast by chance. It’s the combination of a flat, straight course, mild weather, a softer surface, a history steeped in records, and meticulous organization—the hallmark of German precision. Everything here is designed to help runners, whether elite or amateur, push beyond their limits. Every September, the Brandenburg Gate becomes the stage for performances that redefine what’s possible. The only question is: who will etch their name into history this year? In Berlin, more than anywhere else, the impossible suddenly feels within reach.

Clément LABORIEUX

Journaliste