Climbing Mont Ventoux: Harder by Bike or on Foot?

Last July, the riders of the Tour de France tackled the legendary Mont Ventoux for the 18th time in the history of the Grande Boucle. Stage 16, from Montpellier to the summit of the “Giant of Provence,” turned into an epic battle that ended with Frenchman Valentin Paret-Peintre triumphing over Irishman Ben Healy after a nail-biting finale. Just a few weeks earlier, nearly 1,500 runners had tested themselves against the same slopes during the Mont Ventoux Kookabarra Half Marathon. So which is tougher: reaching the top by bike or on foot? To find out, Marathons.com took on the climb by bicycle, while Manon Coste, winner of the 21 km race at the 2025 edition, shared her thoughts on the run.

Mont Ventoux, a true legend made famous by the world of cycling. Rising to 1,909 meters (6,263 ft) in the Vaucluse region of southern France, this mountain stands apart and continues to fascinate athletes. Each year, between 150,000 and 200,000 cyclists take on its breathtaking roads. During the 1955 Tour de France, as the riders approached the climb, Frenchman Raphaël Géminiani famously shouted to his Swiss rival Ferdinand Kübler: “Careful, Ferdinand, the Ventoux is not like any other climb!” A legendary warning that perfectly sums up the brutal difficulty of this ascent.

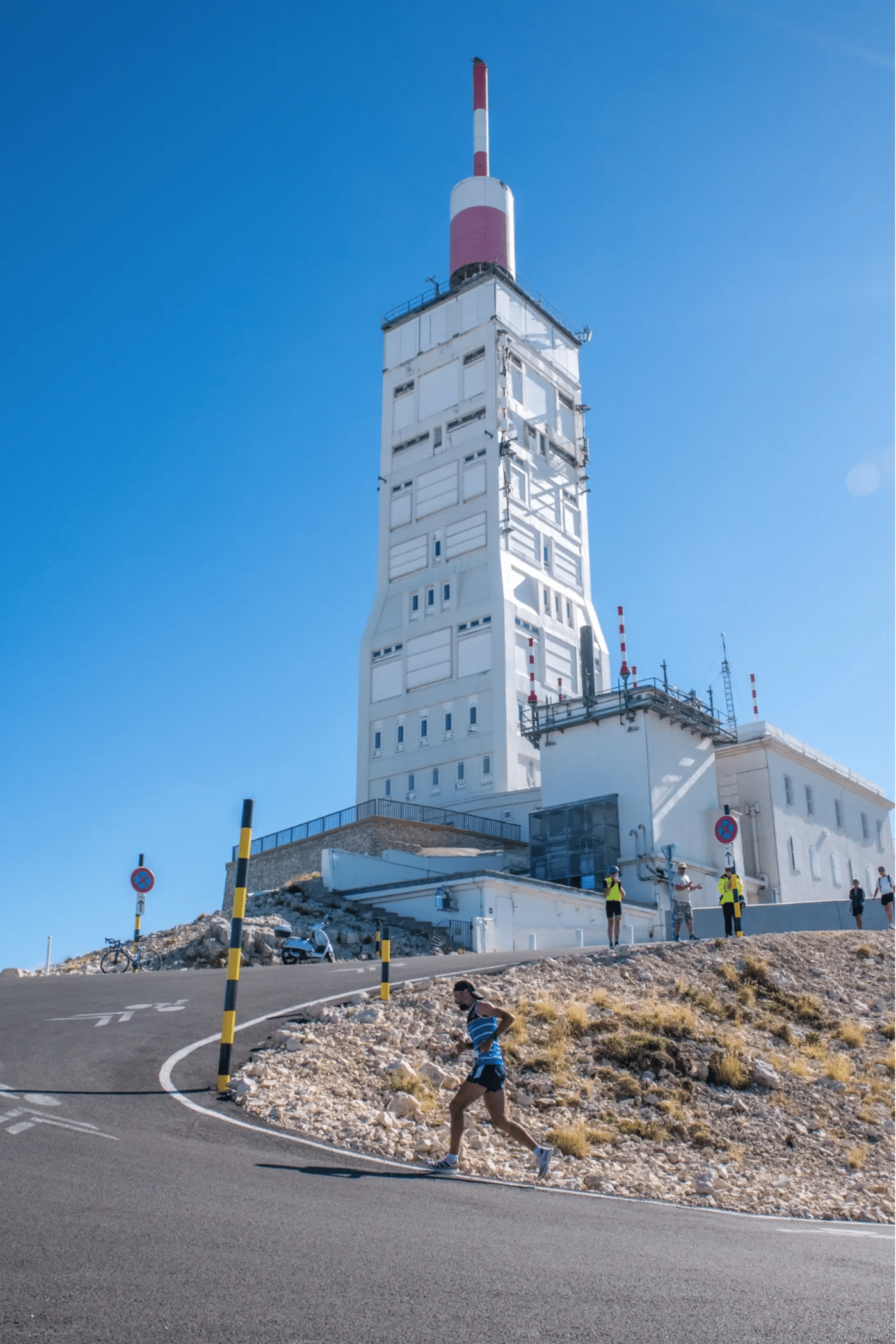

There are three possible routes to reach the iconic red-and-white communications tower at the summit of this hors catégorie giant. The first, and by far the most famous, is the ascent via Bédoin, which has featured most often in the history of the world’s greatest cycling race. The Mont Ventoux Kookabarra Half Marathon also takes place on this side of the mountain and, in 2025, attracted nearly 1,500 participants. It is widely regarded as the toughest half marathon in Europe.

With its 21.6 km climb and 1,610 meters of elevation gain, averaging a 7.5% gradient and including 15.7 km at an average of 8.7% on the Bédoin side, the Giant of Provence more than lives up to its name. The other routes are no easier: from Malaucène, the climb is less uniform but includes brutal ramps (21.1 km, 1,538 m of elevation gain, 7.5% average gradient, with sections hitting 12.7%). The gentlest option is from Sault (25.6 km, 1,216 m of elevation gain, with a 4.5% average gradient). There is even a fourth, lesser-known path, part road and part trail, starting from Bédoin (24.5 km with 1,620 m of elevation gain at an average of 6.7%). Anyone who manages to conquer all three main routes earns the right to join the aptly named “Cinglés du Mont Ventoux” — the “Madmen of Mont Ventoux” club.

The climb isn’t accessible year-round, as the roads to the summit are closed during heavy snow or severe weather. Mont Ventoux is also the realm of the mistral wind, which frequently lashes its merciless slopes and can turn any ascent into a punishing battle on the way to the peak.

| The Ascent by Bike: Stepping Into the Shoes of a Tour de France Rider

Marathons.com took on the climb of the “Bald Mountain” from Bédoin by bike, an unforgettable experience completed at a steady pace in 1:55 (with a companion finishing in 1:25). That’s a far cry from the blistering 53:47 it took Slovenian star Tadej Pogačar to conquer the same route…

The ride began on July 30 at 9:00 a.m. in Villes-sur-Auzon, with a gentle 10 km approach leading to Bédoin. The Giant of Provence, tucked into the Vaucluse mountains, is visible from miles away, towering above the region’s iconic lavender fields, fragrant with their distinctive scent.

From the very first kilometers, you feel as though the climb has already begun, since its silhouette dominates the horizon. Entering Bédoin, a lively Provençal village buzzing with cyclists, motorbikes, and cars, the atmosphere already hints at the challenge ahead. From the hamlet up to Sainte-Colombe, the road climbs gradually, lined with vineyards and cherry orchards. The gradient shifts from 2% to 4%, then 5%, and a little over 6% as you reach Sainte-Colombe, before easing briefly on a short flat stretch.

But at the Saint-Estève bend, where the rocky slopes and pine forest begin, the road suddenly kicks up and hardly lets go until the very top. The mountain that once loomed to your left now stands directly in front of you. It looks almost unreachable, which only adds to its legendary aura—mythical, untamable, and unforgettable.

For 9.5 km at an average gradient of 9.3%, the road to Chalet Reynard—an iconic local restaurant—turns into a brutal test, ramping up from 3% to 9%. It’s a punishing start to the climb, especially since the red-and-white tower at the summit is still far away. The road narrows through a tight gorge, then snakes into the forest, with long straight stretches that seem endless. There’s not a single real respite, as even the “easiest” sections never drop below 8%, while the steepest hit 11%. Even the well-trained Marathons.com riders struggled here, just like the thousands of cyclists of all ages, levels, and nationalities who attempt this challenge every year.

We quickly found ourselves grinding away on the smallest cogs of a 34-tooth cassette—and stayed there for quite a while, pushing hard. We even saw some riders turn back or put a foot down at this stage. This stretch is long and mentally draining. All around, nothing but dense Provençal vegetation fills the view. One upside: the road is cyclist-friendly, with plenty of bins along the way to toss empty gel and bar wrappers. As the kilometers tick by, the trees thin out and endless stone fields take over, a clear sign of the rising altitude.

The first chalets appear on the horizon, and suddenly the Bald Mountain lives up to its name. The scenery transforms dramatically. These shifts in landscape mark the journey with natural surprises worth savoring. The view is breathtaking: trees give way to brilliant white limestone, creating an arid, almost lunar landscape, stark and unique in its beauty. You may even encounter flocks of sheep wandering across this otherworldly terrain—sometimes right in front of your wheels.

The gradient eases slightly on the way to Chalet Reynard, which sits at a wide bend where the road from Sault joins the climb. The curves open up to sweeping panoramic views, with slopes between 5% and 8%. The summit looms in the distance, still seemingly perched far above. This stretch is unforgettable, deeply moving—every determined rider is awestruck by the magical scenery. It feels unlike any other mountain pass we’ve ever climbed. From Chalet Reynard to the top, there are 6 km averaging 8%. In the final 2 km, the gradient stiffens and the wind grows stronger. Here you pass the memorial to British cyclist Tom Simpson, who tragically died of a heart attack during the 1967 Tour de France.

The experience on this final section varies depending on the sun, the force of the mistral, and your own exhaustion. Exposed at last to the full force of the wind, no longer sheltered by the northern slope, you can easily feel destabilized. In the last kilometer, as you approach the Col des Tempêtes, the road swings left and keeps climbing toward the tower. The final 800 meters are brutal, pushing beyond a 10% gradient. But at the summit, the breathtaking view makes every ounce of effort worthwhile.

| The Ascent on Foot: Conquering It with Legs and Mind

The 2025 edition of the Mont Ventoux Kookabarra Half Marathon was won by Emmanuel Roudolff Lévisse and Manon Coste. A member of Team Mv Thermique, Coste boasts impressive times of 33:35 over 10 km, 1:14:34 for the half marathon, and 2:42:26 in the marathon. Also a duathlete and a physical education teacher, she excels in both disciplines. After conquering the Bald Mountain with a winning time of 1:48:29, she explained that she had completed the half marathon before tackling the climb again the next day—this time by bike. “I actually found the ascent easier on foot.

On the bike, it felt endless, and the slopes seemed steeper than when I was running. Muscularly, the Mont Ventoux Half Marathon felt easier than a flat 21 km, since there’s less muscle damage. It’s really all about managing heart rate. I stuck to my marathon HR, making sure not to spike too high, because once you’re climbing, you can’t bring your heart rate back down.”

“I actually found the ascent easier running. On the bike, it felt endless, and the slopes looked steeper than they did on foot. Muscularly, the Mont Ventoux Half Marathon felt easier than a flat 21 km, since there’s less muscle damage—it’s mostly about managing heart rate.”

Manon Coste, winner of the 2025 Mont Ventoux Half Marathon

The Dijon native enjoys this kind of effort management, though she admits it was made easier by the fact that she was running alone in the lead. “If I’d had to fight for position, it might have been different. I didn’t prepare for it specifically, and I didn’t find it especially hard. On the bike, I probably had a skewed perception, as I realized the day after the race that my gearing wasn’t really suited for the climb. I think it’s easier on foot. I’m used to mountain passes, and on Mont Ventoux the climb just feels long, with brutal gradients. I’ve done Alpe d’Huez several times by bike, but I’ve also tried it running. Once again, I pushed myself harder on the bike than on foot.”

This impression is shared both by regulars who practice both disciplines and by our own Marathons.com riders. Running makes it easier to adjust your pace when the going gets tough—or even to walk, which is an option you simply don’t have on two wheels. If you don’t push hard enough on the pedals, you risk tipping over. When your heart rate spikes, grinding up increasingly steep slopes on a bike can feel downright hellish, whereas when running you can ease off to recover. That said, if you choose to give everything from start to finish on foot, the suffering can be just as extreme. In that case, both ways of reaching the summit are equally grueling.

When it’s just you and your legs, there’s no need to worry about gears or finding the right cassette. You can settle into whatever stride feels best, without being limited by equipment. That freedom can make you surprisingly competitive—even against those climbing on bikes. For comparison, Manon Coste reached the summit in 1:48:29 on foot and 1:59 on the bike. Of course, her first ascent was in race conditions, while the second was more of a leisurely ride, but it still shows that tackling Ventoux in running shoes can sometimes be faster.

That said, cycling feels more enjoyable on the gentler slopes, the flat sections, and especially on the descent. Another advantage for cyclists is that the miles tend to roll by more easily, with a mix of fun and comfort that running doesn’t always offer. On foot, a paved mountain pass can seem even more daunting and punishing, particularly in the heat. On a bike, you suffer less from the sun and feel like you’re covering more ground, moving further and faster.

No matter how you choose to take it on, the effort is nothing short of brutal. Scorching heat, fierce winds, heavy crowds, endless distance—the slopes of the Giant of Provence show no mercy. Reaching the top is an unforgettable experience, packed with raw emotion. The memory of your climb will stay with you long after you leave the Drôme. All that’s left is to try the ascent yourself and see what it feels like.

Emma BERT

Journaliste